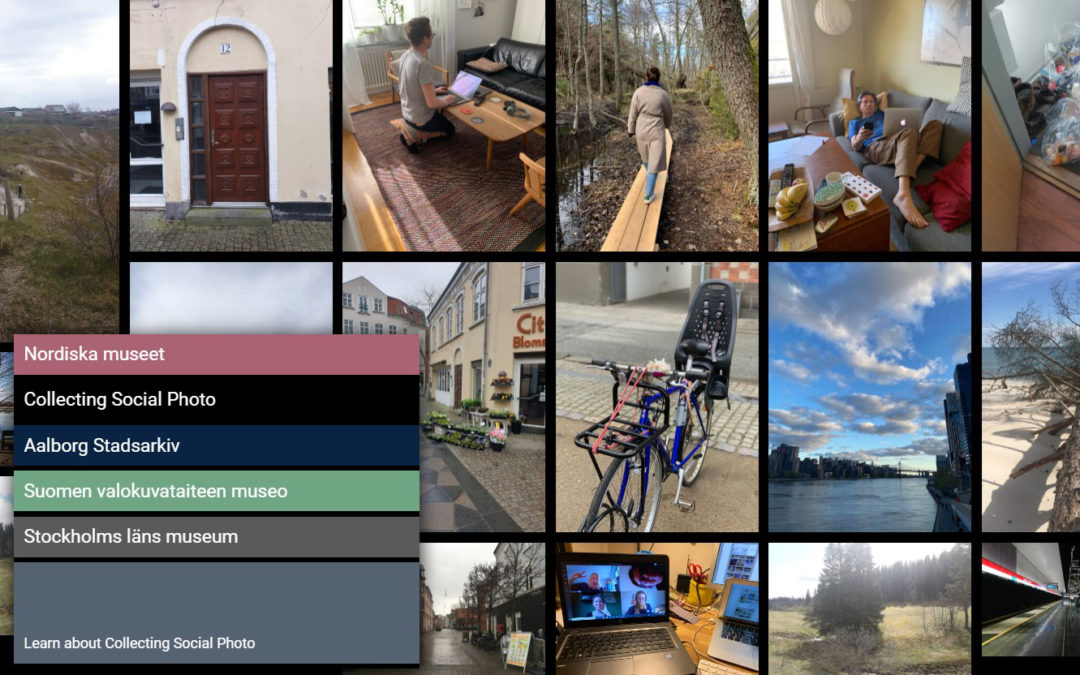

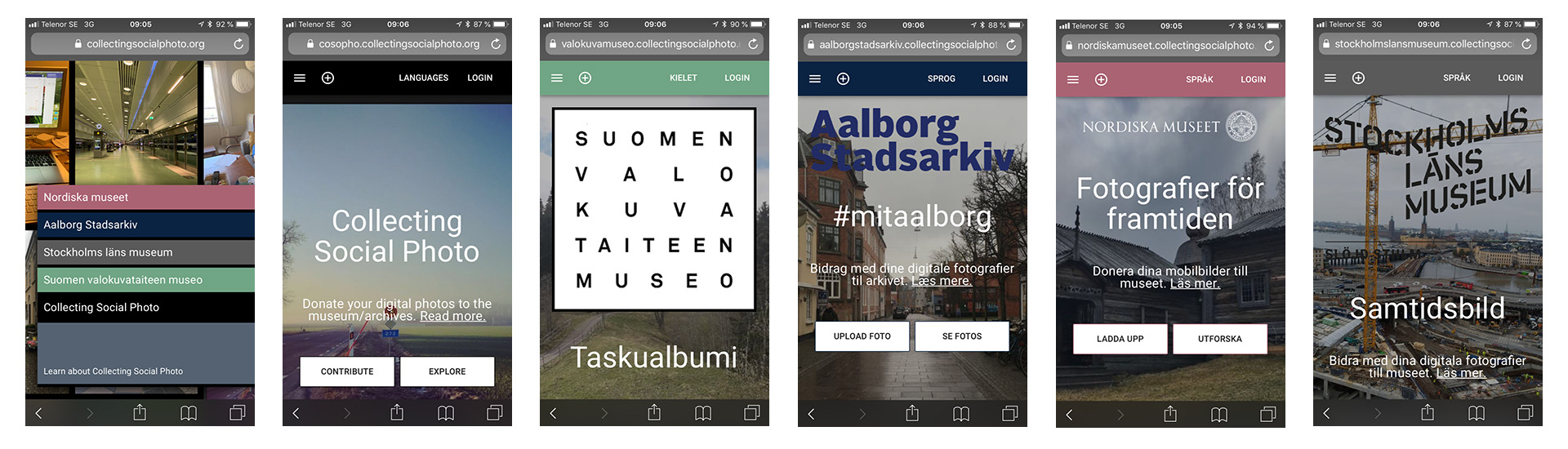

This is an extract, slightly adapted, from the anthology Connect to Collect – Approaches to Collecting Social Digital Photography in Museums and Archives (2020). You can access the web app, one default version and four institutional versions, through www.collectingsocialphoto.org.

Museum collections offer the potential to be the foundations for a rich participatory ecosystem, in which experts and enthusiasts work together to produce knowledge and understanding. That potential has yet to be exploited. Collections instead continue to be presented as “online card catalogs,” even as the rest of the web has transitioned towards participation as an expected norm. Our online collections are more vibrant than ever (better data, better images, more multimedia), but where are the edit and upload buttons?” (Stimler and Rawlinson 2019)

This post aims to introduce the prototype web app that has been developed by the Collecting Social Photo (CoSoPho) project in collaboration with Micah Walter Studio in New York. It shares the process behind the production and reflects on the role of a specific tool for collecting social digital photography.

Social digital photography is a complex assemblage that needs to be collected and disseminated through digital services. One of the research questions in the CoSoPho project also focused on the dissemination of this type of photography. Collections database interfaces in museums and archives today are very much based on managing and displaying digitised analogue photographs, providing limited possibilities for social digital photographs. Developing a new prototype interface for dissemination of these collections was therefore part of the initial plans of the project.

However, early in the project the focus shifted from dissemination to the entire process of collecting, as it became evident that at all steps the process is highly affected by photographic practices and dependent of tools and technologies. Most museums and archives have collections management systems, but no tools for online collecting. The collections databases are managed by museum and archives staff and do not allow for audiences to contribute, other than sometimes through adding comments and tags to existing records. A very basic impact on collecting from the lack of adequate tools is that online collecting becomes an often-demanding manual process or might altogether prevent collecting.

With the collecting process in focus, the project team decided to develop a prototype web app[1] for collecting social digital photography. At the beginning of the project, two of the participating museums had already developed and implemented websites for collecting photographs and stories, Minnen (www.minnen.se) and Samtidsbild (www.samtidsbild.se). The reason for building a completely new prototype tool for collecting was to allow the project team – from four different institutions and three countries – to start examining the process of collecting, in the context of a collecting tool, together and from scratch.

The web app had to be produced with a long-term and sustainable perspective. This meant that the technology must be open source and it had to be produced with constant development and possible scaling in mind. The tool should be easy to use not only by contributors but also by staff and potential partners wanting to run a collecting initiative. The starting point was to lower thresholds with technology, not to raise them.

Shifting focus from dissemination to the entire process of collecting also allowed the CoSoPho team to look at the merging of collecting and dissemination, tasks that traditionally have been separated in museums and archives. The main argument for this is that giving access to collections creates a context for contributing that is more comprehensible, which in turn creates incentives for contributing photos. It is also a question about trust as contributors can see their photos in the museum/archive context once uploaded. There is no reason to separate the two unless the collected material is not suitable for publishing, in which case it should be accessible in reading rooms only or available for researchers with special permission.

Further impacting the production of the prototype web app was the growing trend in museums and archives to integrate inclusive and participatory methods in their work. In a wider context, this is done for several reasons, such as to enhance learning by participation, to increase participation by marginalised groups and to balance power relations. As is the experience of the CoSoPho project, the use of inclusive methods is especially relevant for collection of social digital photography, or any born-digital material, because of its ephemeral nature but also to enable collection of relevant metadata and to allow for more perspectives and voices in collections. The idea was therefore to create a web app that could be used by communities to contribute directly to the museum/archive collections.

To achieve a relevant tool for collecting social digital photography, working closely across institutions within the research projects as well as inviting input from museums, archives and academic colleagues was essential. This collaboration also aimed to be a starting point for long-term maintenance and development of the prototype.

Framing the prototype

To further understand the way technology, and a prototype tool, could support museums and archives in collecting social digital photography, the project organised two workshops in November 2017 and March 2018. International colleagues from archives, museums and academia were invited to both workshops to help discuss valuable features of the collecting tool and possible scenarios where it could be used. The workshops were led by Professor of Practice in Computer Science, Risto Sarvas, of Aalto University, Finland.

During the two workshops, user-centred methods, such as service design methods,[2] were applied to the problem of designing a collecting initiative specifying the role of technology at various stages. Through fictitious thematic cases the participants, divided into small teams, worked on problem-solving for two days during each workshop.

The process of working with service design methods can be described as follows:

“Beware of functional silos. Aim for multidisciplinary teams and give all experts an equal voice. Rock beats scissors and concrete results beat a pre-defined process. Be holistic, see the bigger context. Embrace uncertainty. Co-design with customers. Maximise realism to overcome self-deception. Always validate = Learn, Measure, Build. Have an open and curious mind. Have fun while working.” (Sarvas, Nevanlinna, Pesonen 2016)[3]

Design thinking, service design and agile methods are slowly finding their way into the museum and archives sector, and they originate from product development and marketing industry from the 1980s onwards. They are human-centred, allowing for anticipation and exploration of the different steps of the collecting process. They are highly focused on value creation, responding to the stakeholders’ question: “What’s in it for me?” They encourage experimentation and user testing, and they provide early results that give a solid foundation for decision-making.

A central conclusion from the workshops was that the actual collecting needs to be deeply embedded in a relevant user experience that stretches far beyond the digital interface and that supports the motivation of the user. The digital tool for collecting is one part of a multifaceted or multi-layered process, and this process needs to support both the work methods deployed by the museum/archives and the experience of the contributors. Furthermore, the conclusions from the workshops emphasised the need for user involvement and for co-creation of heritage collections. This was also confirmed by the results of a parallel survey on Minnen.se, performed by the CoSoPho project, about practices of sharing photographs in social media (see Chapter 3).

Following the two workshops the CoSoPho project launched a call for offers inviting companies to develop a prototype that would enable further exploration of the collecting process. Seven companies responded and, after a selection process, Micah Walter Studio in New York was engaged for the task.

The result is an open source prototype web app that is free to download on Github.[4] The CoSoPho prototype is technical as well as structural and aims to support and encourage museums and archives in taking a step towards collecting social digital photography, and to open up for the public to contribute to our common photographic heritage.

You can access the web app, one default version and four institutional versions, through www.collectingsocialphoto.org.

The following section describes the features of the web app, based on the brief that was sent to the companies responding to the call.

Requirements of the prototype collecting tool

In the call for offers, the basic requirements for the prototype were defined. The prototype should:

- Be easy to use for both users and staff;

- Deliver enough context to the photograph to ensure its value as source material;

- Support participatory collecting methods;

- Meet metadata and file format standards; and

- Connect with existing collections management systems to allow acquisition and integration into existing collections and archives.

Target groups

Following discussions in the workshops leading up to the prototype development assumptions about target groups were made. These assumptions were also based on previous experiences by the participating archives and museums. Groups that were considered important ranged from end users, to collaborating partners, to staff setting up collecting initiatives. The survey about photography practices on Minnen.se (chapter 3) also confirmed the main social media channels used for sharing photographs – Facebook and Instagram – and considered the habits of sharing photos, preserving them and attitudes towards museums and archives collecting social digital photographs.

In the planning leading up to the call for offers and development of the prototype, the following overall traits in target groups were identified as relevant:

- Contributors

The overall target group contributors are single users and communities that museums and archives interact with to encourage contributions to the institution’s photography collections. This group often uses social media to share photographs, they use smartphones to take photos, and they have an interest in cultural institutions. They feel positively about contributing to museum and archives collections or react positively if suggested to do so, but may not have done so previously due to experienced or anticipated difficulty.This target group does not primarily comprise people who are unfamiliar with, and even uninterested in, cultural heritage, museums and archives. The assumption has so far been that with a general tool that is easy to use these target groups can be reached as well but that they require strategic outreach, specific engagement efforts and long-term collaboration. - Ambassadors

In this target group are users that would collaborate more closely with museums/archives in collecting efforts, for example members of communities that will act as ambassadors engaging their communities to participate. These ambassadors might also initiate collecting projects completely run by communities. - Staff at museums and archives

The tool would ideally, at some level, be integrated with existing digital infrastructures and collections management systems to make the process of collecting run smoothly. Museum/archives staff represent a mixture of digital literacy ranging from little or no experience to highly-skilled, and the prototype needed to be accessible for all. Many of the staff members might have low tech skills and little or no experience of administering websites (in this case setting up and managing collecting initiatives) and are inexperienced with collecting digital material. Many are also working with very small budgets, which means the service should demand little external technical support once a collecting project is initiated.

Common in all target groups

Identifying common wants and needs helped with drafting fundamental features that would serve the three target groups:

- A low threshold for participating or using the tool.

- Strong incentives to use the tool.

- Confirmation that using the tool is beneficial for them personally (as contributors or in their professional roles).

Motivation to contribute

To further understand what features should be developed in the web app, the CoSoPho project team explored possible motivations for contributing to museum/archives collections. Building on experiences from online collecting, case studies and bringing in current research on the topic, the team made assumptions around user motivations. These were partly based on the most common reasons for contributing to social media: affection, attention seeking, disclosure (the privacy paradox), habit, information sharing and social influence (Malik, Dihr and Nieminen 2016). The incentives to share in social media were then loosely translated into a museum/archives context as motives to contribute to a collecting initiative:

- Make my voice heard in a public setting: telling stories that may or may not be marginalised. This also aligns with the need for attention seeking.

- Contribute to the common cultural heritage: this might be new groups or people more familiar with museums/archives providing insight through collaboration with museums to develop understanding. This could be an eagerness to share information with others and hopefully sharing with museums/archives could potentially grow into a habit.

- Be recognised by a museum/archive: “I can show my photos in a museum/at the archives.” This corresponds to attention seeking and social influence.

- Save my personal photographs for eternity: my shoebox of photos at the museum/archives benefits from the museum/archives as a safe space. This connects to memory aspects as well as personal habits of saving and sorting photos. This may also be connected to a wish to transfer knowledge to communities and share information with future generations.

During the initial testing of the web app, other concerns became apparent such as a fundamental need for trust and transparency when using the web app, allowing for a sense of control in the uploading process. The incentives to contribute to a collecting initiative were also discussed in the context of trust and equity as the project team was well aware that the tool itself would not increase diversity in collections without proper collaboration, outreach and engagement initiatives.

Ethics

Ethical issues were discussed early in the planning stages. As collecting needs to be done in a secure and trustworthy way, the following questions were addressed in the development process:

- How can we collect sensitive images that are not suitable for being published, but need to be collected anyway? One basic solution was to develop a feature allowing the contributor to ‘send only to archives’, as the default feature would otherwise be to publish the images immediately.

- How secure is the system? Can it be hacked and content downloaded by a third party? Discussions were held around using encrypted cloud services.

- If images that are potentially sensitive are published, can staff unpublish them? Can staff get in touch with the contributor to notify them that the image has been unpublished? Can contributors unpublish images themselves at a later stage?

- How is the contributor informed about the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)? By having terms and conditions as well as a privacy policy in the web app users become aware of how their contributions are used.

- How can we create a trustworthy space online with the web app? Several options were discussed, for example being transparent about how the contributions are and can be used in the future and allowing the contributors to get an overview of their contributions through My page.

What to collect

Once the established target groups were decided upon, decisions were made about what the collecting tool should collect, including:

- Image files[5]

- Screenshots of posted images with comments and likes[6]

- Semi-automatically generated keywords through image recognition tool[7]

- User’s own captions and keywords (tags)

- EXIF data (coordinates, time/date and camera type)

- Ability for people to upload entire Instagram or Facebook accounts (images and .json files) via f.ex. Dropbox[8]

- Other contextual information such as information on social media channels etc.

Images to be collected

A fundamental question for the development of the prototype was to decide on what types of photographs were to be collected. Early on, the project had identified difficulties in collecting straight from social media, as for example Instagram makes regular changes to their API, limiting access to accounts from third-party apps.[9] Another conclusion from the project is that collecting should always be done with the photographer’s consent, for legal and ethical reasons. One solution, apart from asking for photos to be uploaded straight from users’ phones, would be to ask participants to take screenshots from their social media accounts and to upload these. This would require the contributor to add metadata about which platforms they used and asking them to upload the same hashtags. Asking users to download and contribute entire Instagram or Facebook accounts is another option, although it was not included in this version of the web app.

The prototype was aimed at allowing the upload of:

- Digital photographs (from smartphones or other sources) that might or might not have been shared on social media; and

- Screenshots of images posted in social media.

Collecting metadata and personal information

Besides collecting actual image files, the following metadata was deemed to be of interest:

- Responses to questions asked by the museum/archive – connected to current collecting themes;

- User’s own captions and keywords;

- EXIF data extracted from the image file (coordinates, time/date and camera type); and

- Metadata added by staff members to give context to collected photographs and captions.

The aim was also to allow for semi-automatic addition of keywords acquired by running the image through an image recognition service. It was decided to explore experimentation around this through a separate case study, which is accounted for in Chapter 8.

In addition, personal information needed to be collected: users were encouraged to share their age, gender, occupation, place/country of birth and place of living. Collecting this information enhances the quality of the data as it gives basic demographic context to the uploaded content.

Features

Based on discussions around user groups and motivations, along with the needs of the museum/archives for a smooth process of acquiring photographs, the team decided on some basic features that would allow for setting up collecting initiatives using the web app. The features were decided on during a workshop using brainstorming, grouping, prioritizing and revising. This was the result:

- Mobile first

As photographs are mainly taken with smartphone cameras and as a majority of people have access to the Internet through their smartphones, the interface for the web app needed to be adapted to a mobile format. - Desktop access

Administrative tasks by staff, such as setting up a collecting initiative, or administering an ongoing collecting initiative, might still best be done via a desktop computer. Some users might also prefer making contributions from a desktop computer. - Login with social media accounts or email

There is a need for user accounts to allow users to easily access the images they have uploaded. Preferably, those accounts could also be used for one-to-one communication between staff and users. - Uploading of image files (single + batch)

Some users might want to upload only one image. However, in some cases users would want to batch upload many photos from, for example, a significant event. - Edit uploaded images (add metadata, edit EXIF data, etc.)

Once an image has been uploaded, the user might wish to add or change information. This provides a good user experience. However, altering a contributed image and text should not be allowed after a set amount of time, as the image needs to be unaltered once it has been acquired into the collection (exceptions can of course be made after consultation with the museum/archives). - Automatic extraction and addition of EXIF data

Automatic extraction of EXIF data is built into many photo editing services. This would also be useful in a collecting process. The information is valuable to the museum/archives and at the same time not considered relevant to add by the user. - Possibility for museum and archive to add metadata on collection level as well as for unique objects (should be separated from user-generated metadata)

As in traditional ways of describing photography collections by curators/archivists, there is a need for staff to be able to add context from the museum’s/archives’ point of view. In the case of social digital photography, metadata added by contributors themselves might also need to be complemented by expert-led cataloguing to increase accessibility through search functions. From a metadata perspective it is important to be able to separate each addition of metadata with date and creator. See further discussions on the topic in chapter 8. - Adding captions and keywords as spoken words

A suggestion from the international community of museum colleagues was to add a possibility for the user to upload recordings of spoken words. This is a good way to get more information, especially from smartphone users who might not wish to write long captions on their phones but instead make a voice recording. However, this feature was not developed in the first version of the web app. - Terms and conditions

In the process of collecting there needs to be a feature allowing for the user to agree to the terms and conditions of the collecting initiative. This has to be done before uploading the photos. The terms and conditions should regulate the handling of personal information, the further use of the photos and text contributions as well as the actual acquisition of the contributions into the museum’s/archives’ collections.The user agrees on licensing of images to regulate further use of the contributions once acquired by the museum/archives. Published photos should be licensed with a Creative Commons licence.[10] - Publish publicly or send to archives (not public)

One of the incentives to contribute to a collecting initiative is to see other people’s images and to feel a part of a common effort and context. This has been a positive experience from both Minnen and Samtidsbild. However, there are ethically sensitive images that might not be suitable for publishing. This calls for an option not to publish uploaded images, but to send them straight to the archives. If the user chooses not to publish content uploaded through the collecting tool, then the terms and conditions will regulate access to the photos. The terms of access will differ between institutions and sectors. - My pages

To make the contributor comfortable with uploading, as well as with the relationship with the museum/archives, a personal space on the collecting service should be provided. The user can see all their uploaded images and edit them for a short time before they are donated. As an extended functionality, this would be the space where staff could communicate with a contributor around an uploaded image or encourage further participation in other collecting initiatives. However, it was not possible to develop this feature within the scope of the project. - Possibility to download images

As published images are to have an open license, making the content free to be re-used by others, there should also be a feature for downloading images. - Possibility to add metadata later

A feature that was discussed but not developed was the possibility for the user to add metadata at a later date. This would allow for further reflections around an event, for example. This metadata would be dated and separated from the original data. - Moderation after publishing

The prototype needed an admin interface for museums/archives to remove/unpublish content, to create thematic collecting initiatives and to communicate with users.The project team firmly pushed the idea of not moderating content in the web app as this would slow down the process of collecting and negatively impact the user experience. Instead a feature to remove unsuitable content that had already been published was implemented. This also builds on the experience from Samtidsbild and Minnen, where no moderation is used, which has proved to be a very positive experience. Very few contributions have been removed, not because of unsuitable content but to advise contributors that their content might be personally sensitive and should therefore not be published and instead sent to archives only. - Public availability of all images uploaded, should be browsable thematically

The users need to be able to see their photos added to the collections of the museum/archives. This is a matter of trust and a good user experience, but it is also about creating incentives for others to contribute, to be a part of a public photography collection. The intention has not been to create a new social media service, however the tool should make use of common incentives for posting, such as attention seeking, information sharing and to make one’s voice heard in a public setting.

Additional features

A few features were on a wish list to be developed if deemed possible within the time span and budget of the prototype development, such as integration of an image recognition tool and uploading of video. Other features were of interest but it was decided early in the project not to include them due to limited time and budget, such as search functions and parental consent.

Important aspects

A few aspects of collecting and contributing were explicitly mentioned in the product brief. These were expressed to make sure the developer had a user-centred approach.

What’s in it for me?

Throughout the process of collecting, users from all groups would need to have one question answered: ‘What’s in it for me?’ The developer was requested in the offer to specify ideas for how to answer or address the question from all target groups.

Contextual information

As the context of the social digital photograph is vital for building new heritage collections, the developer was to specify in the offer possible solutions for harvesting as much contextual information as possible, user generated and other.

Minimum Viable Product

In the call for offer the developer was asked to suggest a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) based on the brief specifying the prototype. This is a prototype that at a minimum level responds to the needs of the project as specified in the call.

Relevance to museums and archives

One initial requirement was to make sure the prototype was relevant to museums and archives. One aspect of this is usability. A second aspect is a low threshold for getting museums/archives with little or no tech literacy onboard, as well as limited budgets. A third aspect is that the prototype can connect to different museum/archival collections databases. The relevance to the institutional stakeholders had to be at the core of the development process.

Scalability

As developing a prototype is meant to be a first step to a functioning tool, a basic requirement was to make sure the prototype would be scalable. Therefore, the CoSoPho team asked in the production brief that the developer should, in the project report, suggest an exit strategy with a long-term sustainable, viable, scalable future for the interface.

Mobile first

As the project is highly focused on mobile phone photography the user interface had to be developed for the mobile user first. This is also relevant because of the rapid increase in use of the Internet through mobile phones.

Meetings

Throughout the process of the development of the prototype, including regular meetings with the developer was necessary. The project team and the developer need to stay closely in touch.

Deliverables

The primary goal of the prototype development has been to achieve an MVP. This is a product that fulfils the primary goals of the prototype and allows the CoSoPho project team to evaluate and validate assumptions around online collecting, but also a prototype that can be the first step towards producing a more developed product in regular use in museums and archives. A central purpose of the MVP has been to produce it with open source coding and modules, as well as disseminating it openly on GitHub for anyone to download, play with and develop further

Besides the actual prototype, the specification of requirements included the following:

- Connection to API of Minnen.se and a Collective Access database (and possibly a FileMaker database);

- Documentation for the technical development;

- Documentation for the structure and collecting process;

- Suggested further development short-term; and

- Suggested strategies, methods and technical solutions for keeping the data safe during the collecting process.

Results

The CoSoPho project set out to create a prototype tool for collecting social digital photography in the form of a web app. With limited time and resources, a basic prototype, a so-called MVP, was achieved in collaboration with Micah Walter Studio in New York. Micah Walter describes their work with the web app as follows:

The Collecting Social Photo web application is meant to be useful at the scale of many institutions. After working with the CoSoPho team, our studio devised a plan to create a highly scalable web app that could be slightly customised by each participating institution and still offer many of the features and capabilities that modern photo sharing applications have been providing for years. We tried to think of it as a ‘Flickr, but for cultural organisations’ and what those differences might look like.

Under the hood, the application has a backend database and management platform. This is where owners of each ‘instance’ can manage the content on their site, it’s users and all the photos that have been uploaded. There is also a front-end which can be modified by each instance owner to allow some basic customisation for branding purposes. This way each institution can have their own instance of Collecting Social Photo, create their own collecting initiatives, and manage their own users, while participating in a larger overall database project.

Finally the application has an interoperable API that means external developers and researchers can access the data collected for us in visualizations and displays of the underlying collections.

Through the process the project team was able to highlight the many and sometimes complex issues connected to collecting social digital photography. As with the actual collecting projects, digital skills within museums and archives are central. Though developing and maintaining products like the web app is rarely an option for single institutions, staff need to be able to write briefs, carry out a dialogue with technical partners and understand the product well enough to give feedback and assist further development.

The CoSoPho project concludes that there are a few issues to discuss when implementing a collecting tool, such as:

- Finding a sustainable, long-term solution for maintaining and developing the service: The goal at this point is to continue collaboration between museums, archives and tech partners around the open source product.

- Acquiring collected material into the collections management systems: This is currently done through a manual process, which needs to become automatic.

- The role of collecting tools as stand-alone products or integrated into collections management systems: Further discussions are needed around the benefits and possible negative aspects of integrating a collecting tool into a collections management system.

- The use of the tool in projects based on participatory and inclusive methods: As discussed elsewhere in this anthology, participation itself is a debated term, and can be performed on many different levels. The role of a collecting tool in participatory projects needs to be further explored.

The web app is now available on GitHub for anyone to download, test and develop: https://github.com/collecting-social-photo and it is available online through www.collectingsocialphoto.org.

References

Malik Aqdas, Amandeep Dhir, and Marko Nieminen. 2016. “Uses and Gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook”. Telematics and Informatics, 33(1), 129-138.

Sarvas, Risto, Hanno Nevanlinna and Juha Pesonen. 2016. Lean Service Creation. Futurice. https://www.leanservicecreation.com/material/LSC%20Handbook%201.82.pdf

Stimler, Neal and Louise Rawlinson. 2019. Where Are The Edit and Upload Buttons? Dynamic Futures for Museum Collections Online. UK. (Accessed 2019-12-15). https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/where-are-the-edit-and-upload-buttons-dynamic-futures-for-museum-collections-online/

Footnotes

[1] A web application, or web app, is a client–server computer programme, accessed through a web browser. A web app is not downloaded and installed on the user’s mobile phone, in contrast to a mobile app. A mobile app is a computer programme or software application designed to be downloaded to and run on a mobile device such as a phone, tablet or watch.

[2] www.leanservicecreation.com, Sarvas, Nevanlinna, Pesonen (2016).

[3] www.leanservicecreation.com (Accessed Dec 18, 2019).

[4] The web app can be downloaded at: https://github.com/orgs/collecting-social-photo

[5] When collecting photos portraying people, legal and ethical aspects should be considered. Institutions are advised to be aware of how GDPR affects collecting, and if there are differences in how legislations is interpreted nationally. Copyright issues should be regulated through terms and conditions in the collecting tool.

[6] When collecting screenshots personal information is collected through image content and visible social media handles. National legislation should be considered. Collecting institutions should also be aware that a comment can be considered to be protected by copyright.

[7] This was originally planned to be a feature of the prototype web app, but it was not possible to implement it due to limited time and resources.

[8] This was not included in the web app due to limited time and resources.

[9] https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/instagram-api-guide (Accessed Dec 28, 2019).

[10] The CoSoPho project chose to use CC0, CC-BY and CC-BY-NC. The reason for the non-commercial license is to prevent images depicting people being used commercially. The use of Creative Commons licenses should be further discussed in relation to collecting social digital photography. For further information on Creative Commons licenses see: www.creativecommons.org